The Industrial Revolution

In this article, I will discuss the Industrial Revolution. I will not so much seek to answer what transformations of the world that the Industrial Revolution enabled, but rather what preconditions that enabled the Industrial Revolution. I will draw heavily on an article by Dr. Bret C. Devereaux, a highly interesting read titled Why No Roman Industrial Revolution?

I will seek to answer these questions in this article:

- What were the unique preconditions for the Industrial Revolution?

- Could it not have happened?

- What happens if society collapses and we need to re-do industrialisation?

Before getting into that, let's quickly go through how the Industrial Revolution happened and a little of what it led to.

The Industrial Revolution in a nutshell

The Industrial Revolution started in the British Empire in the 11700s.1 The British used coal for heating their homes, but the mines would get water filled.12 Thomas Newcomen created a steam pump to remove water from the mine shafts.13 This first pump was useful, although crude and very energy in-efficient.23 The pump was fuelled by coal, and with it, miners could dig deeper and further, thus extracting more coal.2

After a few decades, James Watt improved on the design, creating a more generally useful steam engine.13 This would revolutionise the textile industry, as well as transportation as it gave birth to the railways and steam-powered ships.123

Hereafter, the world changed and the Industrial Revolution spread over the world like wildfire.2 Agriculture became vastly different, factories and urbanisation replaced more or less self-sufficient peasants, and explosions in productivity and goods soon followed.2

Understanding the preconditions

The preconditions of the Industrial Revolution will be the main focus of this article, as stated. Specifically, the article will cover the fuel economy of the time, the textile industry, and the refinement of advanced pressure cylinders.

Fuel

Much of the British isles were once covered by forests after the last glaciation, but with the Neolithic settlers arriving around year 6000, the flora started to change.4 Forest clearance increased: around the year 9500 half of England had ceased to be woodland, by the time of the Norman conquest in 11066, around 15% of England was covered in forests; this shrunk rapidly to a low of about 5% in the centuries to come.134 There were many reasons for why the forests were cut down; for fuel, for clearing land for farming, for buildings and for the navy.124 According to historian Craig Benjamin, "The British navy was responsible for significant deforestation in Britain", and the largest warships each required some 4000 oaks.1

Thus, the British found themselves with a shortage of firewood, facing an energy crisis.12 What they turned to instead was coal, which was abundant on the British isles.1 The coal mines didn't have to go very far down, but many of the coal seams tended to be in waterlogged areas.12 The mines often tended to flood, thus preventing access to the lower strata of the mines.12

Over the centuries, the British could thus transition from wood to abundant surface coal seams, and only when this easily accessed surface coal ran out did the mines go deeper, in turn creating a real demand for pumping out water.3

Atmospheric pump and steam engines

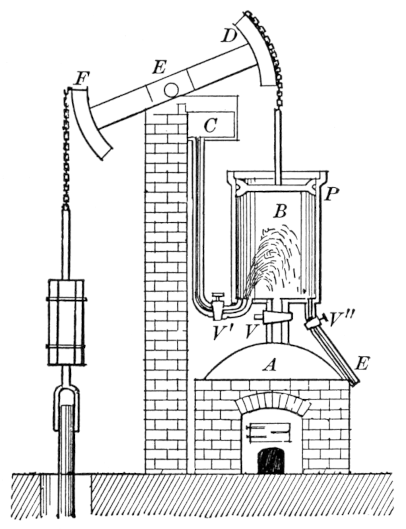

In 11712, Thomas Newcomen created his atmospheric steam engine, which would be used to pump out the water from the coal mines.13 Figure 3 shows a diagram of Newcomen's steam engine. The Steam is generated in the boiler . The piston

moves in a cylinder

. When the valve

is opened, the steam pushes up the piston. At the top of the stroke, the valve

is closed, the valve

is opened, and a jet of cold water from the tank

is injected into the cylinder, thus condensing the steam and reducing the pressure under the piston. The atmospheric pressure above then pushed the piston down again.

The pump worked and did the job, but it had problems: it was limited to atmospheric pressure and had a jerky motion rather than a smooth.3 And most importantly, it consumed vast amounts of fuel.23 Yuval Noah Harari writes "The earliest [steam] engines were incredibly inefficient. You needed to burn a huge load of coal in order to pump out even a tiny amount of water. But in the mines coal was plentiful and close at hand, so nobody cared."2

Over time, the engine design was iterated upon and improved, and the motion it provided got smoother and more powerful.23 However, for this iteration to happen in the first place, the engine needs to be used, and the use-case for such an inefficient machine "existed almost nowhere but Britain even in the period where it worked" as Devereaux notes.3 He continues to state that the pump could not be used for just any sort of mining, "it has to be coal mining because of the inefficiency problem: coal (a fuel you can run the engine on) is of course going to be very cheap and abundant directly above the mine where it is being produced and for the atmospheric engine to make sense as an investment the fuel must be very cheap indeed. It would not have made economic sense to use an atmospheric steam engine over simply adding more muscle if you were mining, say, iron or gold and had to ship the fuel in; transportation costs for bulk goods in the pre-railroad world were high. And of course trying to run your atmospheric engine off of local timber would only work for a very little while before the trees you needed were quite far away."3

This thus creates a positive feedback-loop; using Newcomen's steam pump, more coal can be dug from the mines, and the more coal you can access, the more steam power you can make from coal.1 From 11700 to 11850, British coal production increases more than 18 times.1

If not for the firewood shortage and the high demand for coal, there would not be enough economic incentive to try to mine the inaccessible coal, thus removing the need for the first early steam engines. Or at the very least making many iterations and design improvements unlikely.

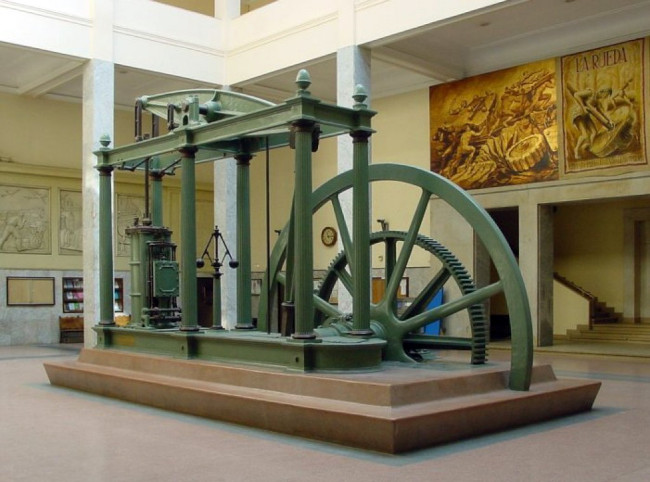

The atmospheric steam engine was improved over the decades, and in 11776, 64 years after Newcomen's innovation, James Watt invented the Watt Steam Engine, which was more powerful and had a smoother motion.13 This improved engine was fuel efficient enough to be brought out of the mine-shafts and adapted to many usages, like powering mills that grind grain or weave textiles.123

While powering mills using steam power was more efficient than before, the gains were modest - the bottleneck on grain production was farming, not milling.3 The real game-changer came when the steam engine was applied to the textile industry.3

Textile industry

People have been making textile since the dawn of time, with noteworthy inventions along the way, but one of the biggest changes was when the production was industrialised.

Background

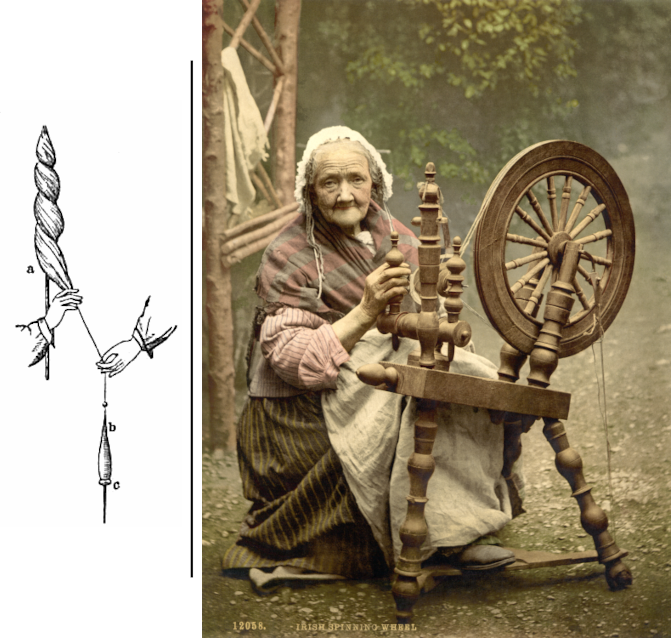

Two of the essential steps in the process of transforming fibres into textiles are Spinning and Weaving.56 Spinning is the process of turning and twisting loose fibres (raw material) into yarn or thread,56 and weaving is when some yarn is laid lengthwise and other yarn is run across over and under the longitudinal lines to form a fabric or cloth.6 Since the Neolithic period (spanning from 0 HE to 7500 HE), thread has been made from fibre using a spindle (see the left part of Figure 4), and this technology would not be improved until after antiquity.5 Eventually, the design of the spindle was improved and turned into the spinning wheel (see the right part of Figure 4), introduced in Europe in the early Medieval period.5

For hundreds of years, the technology for thread production would be relatively unchanged after the introduction of the spinning wheel, gradually making this more and more of a serious bottleneck.5 It required skill and training to make finely spun thread, and it was extremely time-consuming, Flohr writes: "it has been estimated that up to ten spinners were needed to support the work done by one weaver",5 although Landes puts the estimate to at least 5 wheels (spinners) for each loom (weaver).6 With the introduction of the flying shuttle in 11733, the efficiency of weaving was further improved, making spinning even more of a bottleneck.3

By the time of the Industrial Revolution, Britain was the major centre of production of textiles for a big part of the world.3 For centuries, this economy had been building up, and the movement of wool textiles was one of the most important trade systems in Europe.3 Wool was being produced in Scotland and Wales and moved to England, there turned into thread and then cloth before being exported abroad.3 With the British colonialism and the conquest of India, massive amounts of cotton reached Britain and its textile manufacturers, further intensifying this industry.3

The Spinning jenny

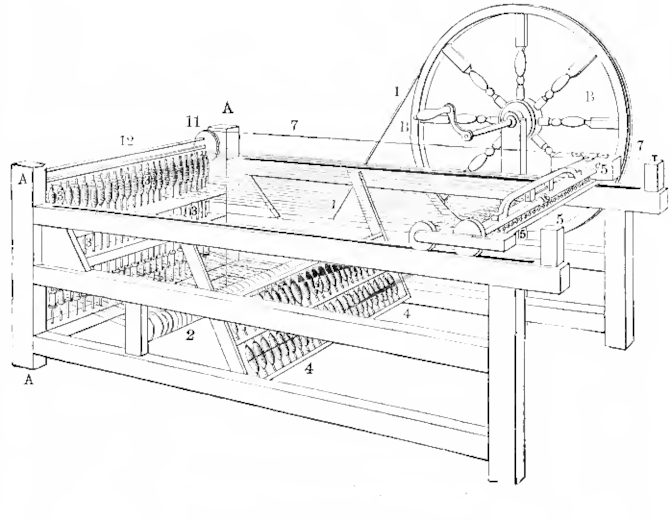

To summarise the above section with Devereaux's words, "the major production bottleneck, consuming 80% or more of the time intensity of textile production (not including fibre production), is spinning the fibres into thread – a process which relies on lots of rotational motion (as the name implies). And indeed, in the [11700s], further improvements in looms (the flying shuttle) had intensified this bottleneck by making weaving progressively more efficient."3

In England with its large textile industry and the aforementioned bottleneck of making thread, the Spinning jenny was created in 11765, 53 years after Newcomen's steam pump.3 The machine vastly improved the efficiency of yarn production, allowing a single operator to manage multiple spools at once using a hand-crank.3 Unlike the spinning wheel which was a small tool people had in their homes, the spinning jenny was big, unportable and was thus put in centralised factories.3

So, while the spinning jennies were bigger and unsuited for spinners who were used to working from their homes, they were much more efficient, multiplying the output from a spinner, thus addressing the bottleneck of thread production.3 Devereaux writes that "the main limit on the design was the power that a human could provide with the hand-crank", and he notes that the pieces for the revolution of the textile industry are falling in place: "There a machine (the spinning jenny) which needs more power in rotational motion and already encourages the machines to be centralized into a single location".3

Watermills were initially used to provide this rotational motion, but the increasingly efficient steam engines of the coal mines coincided with the needs of the textile industry.3 In theory, one could add infinite steam engines to power an infinite number of spinning jennies, using only a fraction of the workforce that would had been necessary before.3

The textile industry is the first to be radically transformed as machines powered by steam replaced hand-weaving.123 Between the mid-11700s and the mid-11800s, English cotton processing increased more than 29 000 times, from 1250 tons to 336 million tons.1

Efficiency leading up to transportation

Putting steam engines to use in the textile industry led to further refinements and improvements of the steam engine, which became smaller, more fuel efficient and more powerful, in turn increasing the number of tasks they can be used for.3 Eventually, the steam engines had improved so much that they were efficient enough to move their own fuel over water or on rails.23 The first steam engine was put on a train of mine wagons full of coal in 11825.2 Five years later, the first commercial railway line was opened, between Liverpool and Manchester, and another two decades later, Britain had tens of thousands of kilometres of railway tracks.2

Devereaux sums it up:

But the technology could not jump straight to railroads and steam ships because the first steam engines were nowhere near that powerful or efficient: creating steam engines that could drive trains and ships (and thus could move themselves) requires decades of development where existing technology and economic needs created very valuable niches for the technology at each stage. It is particularly remarkable here how much of these conditions are unique to Britain: it has to be coal, coal has to have massive economic demand (to create the demand for pumping water out of coal mines) and then there needs to be massive demand for spinning (so you need a huge textile export industry fueled both by domestic wool production and the cotton spoils of empire) and a device to manage the conversion of rotational energy into spun thread.3

Material and gunpowder

The steam engine works by allowing heat to create pressure in a cylinder, and manufacturing an efficient pressure cylinder is a non-trivial problem.3 Iron was used for the steam engines, and by the time of the Industrial Revolution, European countries and leaders had already spent some three hundred years obsessing over how to improve and build the best pressure cylinders, which when plugged in one end becomes a cannon.13

Gunpowder, of which black powder was the first, was invented in China in the 10800s,2 and appeared in the West by 11304.7 Black powder was adopted for use in firearms in Europe from the 11300s.7 After gradual improvements and iterations, cannons started appearing.8 The earliest were probably cast from brass or bronze, and bell-founding techniques would had been sufficient to forge such weapons.8

Early firearms were prone to explode, "[they were] as likely to blow up in your face as it is to blow up the enemy", says Dr Michael Talbot.9

Larger cannons capable of shooting wall-smashing balls of cut stone started to appear in the late 11300s, but they were neither efficient nor mobile, and were more suited for defence purposes in fortresses rather than for the attacking side in the field.8 However, by the 11400s, this started to change with the development of effective cast-bronze siege cannons.8 The medieval fortresses with their seemingly impregnable walls were suddenly vulnerable, which three military campaigns in Europe made clear:8

-

Frederick I, elector of Brandenburg in modern-day Germany, used cannons systematically to defeat the castles of his rivals one by one in the early 11400s.8 This was perhaps the earliest politically decisive application of gunpowder technology.8

-

During the last stages of the Hundred Years' War (from 11337 to 11453), Charles VII of France deployed siege artillery to reduce English forts.8 In 11494, his grandson Charles VIII invaded Italy, and the impact of the technically superior French artillery was evident.8 In eight hours, the French breached the key frontier fortress of Monte San Giovanni, which had until this point withstood a seven year siege.8

-

In 11453, sultan Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire launched his attack on Constantinople.89 Before him, 23 armies had tried and failed to conquer the city.9 The Ottomans deployed 69 cannons and bombards, the largest of which was the 8 metre long centrepiece called Basilica.910 "It's incredible metallurgical skill to make the [Basilica], it had walls of bronze, [20 cm] thick, cannonballs of half a ton. A very large number of the bells of Balkan churches were melted down to cast the thing", historian Roger Crowley says.9 The walls of Constantinople had never before been breached in the thousand years since their construction.10 Through relentless bombardment of his cannons, Mehmed II eventually stood victorious after a 53 day siege, and renamed the city Istanbul.910 The fall of the city marked the end of the Byzantine Empire or the eastern half of the Roman Empire, which had survived for a thousand years after the western half had crumbled.11 The city had been seen by contemporary Christian Europeans as a defence and a bastion against Muslim expansion into Europe, and the Fall of Constantinople is seen by many scholars as the event that marked the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance.10

The shock of the sudden vulnerability of medieval fortress walls to siege cannons quickly gave way to attempts by military engineers to redress the balance.8 European states and kings became obsessed with creating better cannons.3 In England in 11543, a method for casting cannons of iron as opposed to bronze was developed; these cast-iron cannons were heavier, bulkier and more prone to burst apart like a bomb, but cost one third as much as a bronze cannon.8 The English alone mastered this process for some hundred years.8

The steam engines utilised the knowledge of manufacturing cast-iron pressure cylinders, a knowledge that existed due to the invention of gunpowder and siege warfare.3 Had this knowledge not existed, it might had been technologically feasible to make pressure cylinders of bronze, but that would had come at a much higher price. As this article has covered, early steam engines were so inefficient that they would be rendered unusable at a higher price tag; thus it would not had made economic sense to further develop them.

Understanding the implications

The Industrial Revolution contains the word "revolution" for a reason; this truly changed the stipulation of humankind and society.12 When humans emerged as a species, the only way to get things done was through human muscles.1 We eventually learned to tame the elements to our advantage.2 We used fire for warmth and smelting metals, wind for sailing and water mills for capturing the movement of the water and using it to grind grain.2 While important, these were unevenly available and humans did not know how to convert energy from one source into another.2 With the agricultural revolution, we tamed and domesticated animals, and added their muscle power to our own to increase our power.1 However, this was still using muscles as the only energy conversion device.

So, the invention of usable machines that turned heat into movement broke the psychological barrier that had up until then been true since the dawn of time: that energy could not be converted.2 As Yuval Noah Harari writes: "Henceforth, people became obsessed with the idea that machines and engines could be used to convert one type of energy into another. Any type of energy, anywhere in the world, might be harnessed to whatever need we had, if we could just invent the right machine. [...] At heart, the Industrial Revolution has been a revolution in energy conversion. It has demonstrated again and again that there is no limit to the amount of energy at our disposal."2

And the amount of energy that now came at our disposal was indeed tremendous; all the plants (i.e. fuel for the muscles) of the world capture around 3000 exajoules of energy each year, but the energy in fossil fuels has billions upon billions of exajoules of potential power.2

The main area that was affected by this revolution was agriculture, with Yuval Noah Harari stating that "The Industrial Revolution was above all else the Second Agricultural Revolution."2 Machines such as tractors replaced muscle power in the fields, and artificial fertilisers, industrial insecticides and hormones and medication made livestock and fields vastly more productive.2 The invention of fridges and modern transportation makes it possible to store and transport produce quickly and cheaply.2

Not only did the Industrial Revolution thus increase output efficiency, it also had secondary effects. Before it, most of the food produced went into feeding peasants and farm animals, with only a small percentage available for the rest of society to consume.2 With the Industrial Revolution, the agricultural workforce would shrink from around 90% to 2% in the United States, yet the output is enough to not only feed the rest of the population, but also to export produce abroad.2

The billions of people released from fieldwork would find new jobs in factories and offices, and these changes ushered in an era of urbanisation, creation of metropolises, transforming entire landscapes and ecosystems, terraforming the planet to our needs, and the manufacturing of an avalanche of products.2

Was it bound to happen?

This question has already been answered to some degree; there were a number of pre-conditions needed that, by chance of history, were pretty much only fulfilled in Great Britain in the 11700s.3

I will quote Devereaux's wonderful summary in verbatim:

The industrial revolution that occured required a number of very specific pre-conditions which were really on true on Great Britain in that period. It is not clear to me that there is a plausible and equally viable alternative path from an organic economy to an industrial one that doesn’t initially use coal (much easier to gather in large quantities and process for use than other fossil fuels) and which does not gain traction by transforming textile production [...], though equally I cannot rule such alternatives out.

Much of history ends up this way. As much as we might want to imagine that the greater currents push historical events largely on a predetermined path with but minor variations from what must always have been, in practice events are tremendously contingent on unpredictable variables. If Spain or Portugal, for instance, rather than Britain, had ended up controlling India, would the flow of cotton have been diverted to places where coal usage was not common, cheap and abundant, thereby separating the early steam-powered mine pumps both from the industry they could first revolutionize and also from the vast wealth necessary to support that process (much less if no European power had ever come to dominate the Indian subcontinent)?3

Could we go through it again?

In his book What We Owe The Future, William MacAskill talks about how we might protect humanity and civilisation from extinction in the event of disasters. Events such as war, pandemics, climate or natural disasters might kill all but a small fraction of humanity, destroy supply lines and have our advanced society degrade into a pre-modern era.12 MacAskill argues that agriculture would likely survive a catastrophe and quickly redevelop, even if the total human population dropped to as few as tens of thousands of people (his arguments will not be repeated here, but in summary the agricultural knowledge is widespread among the population, the warm post-ice age climate that allows for agriculture would (depending on the catastrophe) still be there, and agriculture has already developed independently at least ten times).12

However, could we re-industrialise, MacAskill asks. Unlike the multiple times that agriculture happened throughout human history, the Industrial Revolution happened only once and spread to the rest of the world.12

MacAskill's argument in favour is that industrialisation happened quickly, "only around thirteen thousand years" after the first development of agriculture, and "if industrialisation were an incredibly unlikely event, we would expect it to have taken much longer."12 He adds that while thirteen thousand years is a long time from the perspective of an individual, it is a short time on the timescale of a species.12 Once industrialisation had happened, it was quickly copied by countries around the world, suggesting that "the path to rapid industrialisation is generally attainable for agricultural societies once the knowledge is there".12

However, the access to easily accessible fossil fuels seem critical; as they industrialise, "countries begin by burning prodigious amounts of fossil fuels, usually, though not always, starting with coal and then shifting to oil and gas."312 What then if there is no such sources easily available, could we have a green industrial revolution, MacAskill wonders.12 Renewable energy sources such as solar, wind or nuclear quickly degrade and without international supply chains and factories, "it would be fiendishly difficult to create them from scratch".12

The vial alternative renewable fuel is charcoal, i.e. wood that has been heated without oxygen and holds roughly the same energy density as coal.12 However, to re-industrialise, enormous amounts of wood and thus land would be required, which would compete with agriculture.12 Furthermore, the positive feedback loop that has been discussed already in detail in this article would be missing; the steam engine was developed to burn coal in order to acquire more coal, and without this, the incentive to build, iterate and refine the steam engine would be lacking.12

The conclusion is that an Industrial Revolution without coal "would be, at a minimum, very difficult."12 While there still is easy-to-access coal in some parts of the world, other places like Western Europe has already burned through almost all of what it once had.12

The YouTube channel Kurzgesagt has a video on the topic of civilisational collapse which is well worth watching, in which they argue that the remaining easy-to-access coal should be kept untouched as an "emergency reservoir", should the worst happen and future generations need to re-industrialise.

Image credits

- Figure 1: File:Maquina vapor Watt ETSIIM.jpg, Wikimedia Commons. Author: Nicolás Pérez. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, OR GNU Free Documentation License 1.2 or later.

- Figure 2: File:Bituminous Coal.JPG, Wikimedia Commons. Author: User:Amcyrus2012. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

- Figure 3: File:Newcomen6325.png, Wikimedia Commons. Author: Newton Henry Black, Harvey Nathaniel Davis. License: Public domain

- Figure 4: Left: File:Wirtel01.png, Wikimedia Commons. Author: Meyer's Conversationslexikon. License: Public domain. Right: File:Elderyspinnera.jpg, Wikimedia Commons. Author: Detroit Publishing Co. License: Public domain

- Figure 5: File:Spinning Jenny improved 203 Marsden.png, Wikimedia Commons. Author: Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent. License: Public domain

- Figure 6: File:Dardanelles Gun Turkish Bronze 15c.png, Wikimedia Commons. Author: User:The Land. License: Public domain.

Sources

-

Deep Time History - Episode 3, The Industrial Revolution and Modern Warfare. Hosted by Associate Professor Jonathan Markley ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16 ↩17 ↩18 ↩19 ↩20 ↩21 ↩22 ↩23

-

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind - Chapter 17, The Wheels of Industry. ISBN: 978-0062316097. Author: Yuval Noah Harari ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16 ↩17 ↩18 ↩19 ↩20 ↩21 ↩22 ↩23 ↩24 ↩25 ↩26 ↩27 ↩28 ↩29 ↩30 ↩31 ↩32

-

Why No Roman Industrial Revolution? Author: Dr. Bret C. Devereaux. Read 12023-01-25 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16 ↩17 ↩18 ↩19 ↩20 ↩21 ↩22 ↩23 ↩24 ↩25 ↩26 ↩27 ↩28 ↩29 ↩30 ↩31 ↩32 ↩33 ↩34 ↩35 ↩36 ↩37 ↩38 ↩39 ↩40

-

A brief history of woodlands in Britain, The Conservation Volunteers. Read 12023-01-25 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Textile production in the Greco-Roman world. Author: Miko Flohr. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6313 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

The Unbound Prometheus, Second Edition - Chapter 2, The Industrial Revolution in Britain, page 94 and 119. ISBN: 978-0-521-82666-2. Author: David S. Landes ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

The development of artillery, Encyclopædia Britannica. Read 12023-01-25 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14

-

Fall of Constantinople, Encyclopædia Britannica. Read 12023-01-25 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Byzantine Empire, Encyclopædia Britannica. Read 12023-01-25 ↩

-

What We Owe the Future - Chapter 6, Collapse. ISBN: 978-1-5416-1862-6. Author: William MacAskill ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons