Der Steppenwolf

Quite a long time ago, perhaps a decade, I by chance stumbled upon a music piece on YouTube. There was something in the melody that captivated me, but more so the sampled German audio. It spoke to me with power, its message resonated with me, yet was short enough to leave a trail of curiosity behind. All this was contrasted with the calming music that made up the canvas behind it.

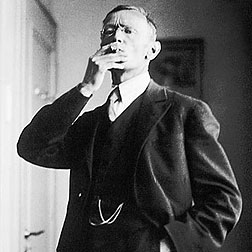

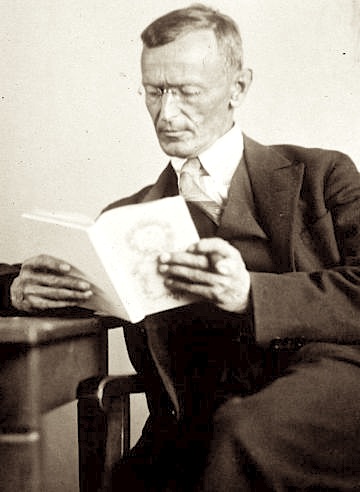

The short German audio turned out to be sampled from Hermann Hesse's novel Der Steppenwolf, published in 1927 and read by Will Quadflieg. The story in large part reflects a profound crisis in Hesse's spiritual world during the 1920s. Fittingly, the novel mostly deals with the inner life and persona of the main character; to a lesser degree any events actually happen.

Plot

The novel is about a man soon to reach his fifties named Harry Haller, an alter ego of the author. He is a man with two natures — on the one hand he is a man, a learned intellectual, who strives for sophistication and spirituality; on the other hand he is a Steppenwolf — a wolf from the steppes — lonely, primitive and animalistic. Whenever the man in him enjoys refined cultural expressions, the wolf stands behind his shoulder and scorns his pretentious self; in the eyes of the wolf, the human devotions are absurd and vain. Whenever the wolf is indulging in its more animalistic sides, the man in him looks down on the wolf with contempt at the primitiveness of it, calling it brute and beast. Harry thus finds himself in a state of constant self struggle, in turn causing his inner life to become reduced to an overflowing cauldron of self-loathing.1

He experiences days that are unremarkable as he lets them go by, aimlessly killing time by the looks of it. The days that he lives out in the start of the novel are "the moderately pleasant, the wholly bearable and tolerable, lukewarm days of a discontented middle-aged man; days without special pains, without special cares, without particular worry, without despair; days when I calmly wonder, objective and fearless, whether it isn't time to follow the example of Adalbert Stifter and have an accident while shaving". While this is indeed on the one hand a vast improvement over days with pain, it is also to Harry intolerable; content and meaningless days drain the very life-blood out of him. "But the worst of it is that it is just this contentment that I cannot endure. After a short time it fills me with irrepressible hatred and nausea. In desperation I have to escape and throw myself on the road to pleasure, or, if that cannot be, on the road to pain. When I have neither pleasure nor pain and have been breathing for a while the lukewarm insipid air of these so-called good and tolerable days, I feel so bad in my childish soul that I smash my moldering lyre of thanksgiving in the face of the slumbering god of contentment and would rather feel the very devil burn in me than this warmth of a well-heated room. A wild longing for strong emotions and sensations seethes in me, a rage against this toneless, flat, normal and sterile life. I have a mad impulse to smash something, a warehouse, perhaps, or a cathedral, or myself, to commit outrages. [...] For what I always hated and detested and cursed above all things was this contentment, this healthiness and comfort, this carefully preserved optimism of the middle classes, this fat and prosperous brood of mediocrity".

Harry is withdrawn from society and lives a solitary life. The novel takes place in a small German town, but it is said that he tends to travel around between towns and villages, staying only a few months at a time in one place, and his custom is to rent rooms and lodging in bourgeois homes. With mainly contempt but perhaps also a bit of jealousy he looks upon his peers in the bourgeois. He lives among them and is drawn to their homes like a moth to a flame; the character himself acknowledges that he has contradicting feelings to the situation. His love of the bourgeois orderly and tidy homes comes from his childhood and a yearning for something homelike, and he enjoys the sharp contrast between the tended orderly home with his own hunted and disorderly existence. "There is something in it that touches me in spite of my hatred for all it stands for". Indeed, his presence among the bourgeois is that of a chameleon or perhaps a cuckoo; he is an utter stranger to their world and looks on it from within without grasping any of it or indeed why it is desirable.2 The contrast between the bourgeois and Harry is a constant throughout the novel, which offers the following definition of the former: "Now what we call "bourgeois," when regarded as an element always to be found in human life, is nothing else than the search for a balance. It is the striving after a mean between the countless extremes and opposites that arise in human conduct. The absolute is his abhorrence. He is ready to be virtuous, but likes to be easy and comfortable in this world as well. In short, his aim is to make a home for himself between two extremes in a temperate zone without violent storms and tempests; and in this he succeeds though it be at the cost of that intensity of life and feeling which an extreme life affords. A man cannot live intensely except at the cost of the self. Now the bourgeois treasures nothing more highly than the self (rudimentary as his may be). And so at the cost of intensity he achieves his own preservation and security. His harvest is a quiet mind which he prefers to being possessed by God, as he does comfort to pleasure, convenience to liberty, and a pleasant temperature to that deathly inner consuming fire. The bourgeois is consequently by nature a creature of weak impulses, anxious, fearful of giving himself away and easy to rule."

Harry's days are spent doing things he finds worthwhile, such as reading old books and poetry, writing columns to papers and conducting research in areas of his interests, and "yearning after a new orientation for an age that has lost its bearings". However, he does so without any pretence of accomplishing much, neither for his peers nor for himself. This is likely another source of his self-deploration; "No, I did not regret the past. My regret was for the present day, for all the countless hours and days that I lost in mere passivity and that brought me nothing, not even the shocks of awakening". Harry has a deep yearning for what he calls "the Immortals" — authors of timeless masterpieces who reach nothing short of a Platonic ideal of authorship, and he wishes to join the ranks of the great, but his inner struggles are holding him back. He looks with awe at Mozart and Bach and Goethe, but apart from these true masters, nothing can withstand scrutiny. He observes from afar with disdain all contemporary music and art-forms.3 He feels at odds with society, regular people, his acquaintances and the times themselves.4 He now and then enjoy culture that bring experiences of such height that he speaks about it in terms of the divine. However, "it is hard to find this track of the divine in the midst of this life we lead, in this besotted humdrum age of spiritual blindness, with its architecture, its business, its politics, its men! How could I fail to be a lone wolf, and an uncouth hermit, as I did not share one of its aims nor understand one of its pleasures? I cannot remain for long in either theater or picture-house. I can scarcely read a paper, seldom a modern book. I cannot understand what pleasures and joys they are that drive people to the overcrowded railways and hotels, into the packed cafés with the suffocating and oppressive music, to the Bars and variety entertainments, to World Exhibitions, to the Corsos. I cannot understand nor share these joys, though they are within my reach, for which thousands of others strive. On the other hand, what happens to me in my rare hours of joy, what for me is bliss and life and ecstasy and exaltation, the world in general seeks at most in imagination; in life it finds it absurd."

As Harry is aimlessly wandering around town, he has a somewhat surreal encounter with a person who gives him a book, the "Treatise on the Steppenwolf". The book addresses Harry by name and gives an uncanny description of him. His dual nature of the man and the wolf of the steppes is described and explained. The book talks about how difficult his interactions with others could be due to his dual nature.5 The Harry described in the book craved independence above all, and had reached it, but at the price of isolation.6

The strange little book goes on to talk about how Harry is one of the so called suicides; unlike what that label might suggest, these are not people who take their lives or plan to do so, but rather those who share "the belief that they have that suicide is their most probable manner of death. [...] they see death and not life as the release". Harry and suicides like him "found consolation and support [...] in the idea that the way to death was open to him at any moment. [...] He gained strength through familiarity with the thought that the emergency exit stood always open. [...] There are a great many suicides to whom this thought imparts an uncommon strength".

Finally, the book describes how Harry's presumed duality of the self is a falsehood. It states that every person is not made up of one unity, nor of two, but of countless. Most people regard themselves as one; those who manage to see that this is not sufficient to describe themselves and rather see two natures in the self are rare — "A man, therefore, who gets so far as making the supposed unity of the self two-fold is already almost a genius, in any case a most exceptional and interesting person". It is rare for this to happen though, "For it appears to be an inborn and imperative need of all men to regard the self as a unit". In the case of Harry, the book explains, "he believes, like Faust, that two souls are far too many for a single breast and must tear the breast asunder. They are on the contrary far too few, and Harry does shocking violence to his poor soul when he endeavors to apprehend it by means of so primitive an image. Although he is a most cultivated person, he proceeds like a savage that cannot count further than two. [...] He cannot see, even though he thinks himself an artist and possessed of delicate perceptions, that a great deal else exists in him besides and behind the wolf. He cannot see that not all that bites is wolf and that fox, dragon, tiger, ape and bird of paradise are there also. And he cannot see that this whole world, this Eden and its manifestations of beauty and terror, of greatness and meanness, of strength and tenderness is crushed and imprisoned by the wolf ledgend just as the real man in him is crushed and imprisoned by that sham existence, the bourgeois."

His mental state is deteriorating, from loneliness and inner struggle. One day, after a funeral (where the mourners and the "clergyman and the other vultures and functionaries" played their parts well, but "nobody wept. The deceased did not appear to have been indispensable"), he walks about town in the "grey streets in a rage and everything smelt of moist earth and burial", disgusted at himself and what he has become.7 However, during his walk in mental despair and social starvation, he by chance meets an old acquaintance; a professor whom he has enjoyed intellectual discussions with in the past. The man invites him over for dinner, and he is relieved to have some sort of comradeship and human interaction to look forward to. However, the evening does not transpire as anyone involved would have wished. Harry is too withdrawn to easily interact with people, and he is too fragile.8 He finds his friend to have a disgustingly nationalistic mentality, unfit in Harry's opinion, for an intellectual and professor. The host also inadvertently criticises a column Harry wrote. Harry on his hand goes into a tirade about how a bust of Goethe that his host has on display, is in bad taste and insulting to the poet's true brilliance. Unbeknownst to Harry, the bust is a very dear possession of the professor's wife, and both the host and guest are left feeling at much unease from the situation. The episode confirms to Harry that he is and will remain a stranger to the society he finds himself in.9

Already at a low point, and with everything seemingly confirming to him that his life is not worth living, Harry knows that what awaits him at home is his razor and death.10 Yet, he wanders around town, aimlessly and with the devil in his heels, trying to postpone what he has already set his mind on. He visits different drinking halls throughout the night, and finally stops in a place where he meets a young woman, Hermine, who recognizes his desperation. They talk for some time, and Hermine seems to read him like an open book, treating him exactly in the way that was best for him at the moment. She mocks his self-pity and the life he's been living ("Fine views of life, you have. You have always done the difficult and complicated things and the simple ones you haven't even learned. But to do as you do and then say you've tested life to the bottom and found nothing in it is going a bit too far"). Her sharpness captures his interest: "I found her charming, very much to my surprise, for I had always avoided girls of her kind". They agree on a second meeting, which gives Harry a reason to postpone the ending of his life.

Over the course of the coming weeks, Hermine enchants Harry, and with her intelligence and charm makes Harry consider things he had not previously been open to. She introduces him to dancing, an activity that he finds deplorable and unsuited for a man of his character. She has him buy a gramophone and practise dancing at home.11 Harry finds Hermine to be a wonderful complement to his own character, and where he is lacking she is strong.12 In his utter desperation, she has come down to him like a seraph from above, but she tells him that just as he needs her, she also needs him. She calmly explains that she needs him to fall in love with her one day, and when that happens, she orders him to take her life. Harry listens and accepts this, almost as if it was fate.13

Hermine introduces Harry to Maria, who, despite not being very far-travelled in the intellectual world, becomes his lover (he however, is but one of her many) and with whom he shares many happy moments. Hermine also introduces him to Pablo, a light-hearted musician. Harry's first thoughts and impression of the man is not high; "Pablo had left on me the impression of a pretty nonentity". Pablo is happy, beautiful, kind and is enjoying life's pleasures, but without much interest in Harry's learned opinions or intellectual endeavours, not even on the subject of music. Harry's view of Maria, Pablo and indeed the whole world gradually changes, however; he experiences deep love with the uneducated Maria, "all her art and the whole task she set herself lay in extracting the utmost delight from the senses she had been endowed with". Harry comes to realise that these are valid experiences of a full life, yet very different from the intellectual toils he had grown accustomed to.

Hermine and Harry meet regularly and share a special bond. Despite Maria being the lover of Harry, Hermine states that neither Maria nor anyone else can understand Harry the way she does. While Hermine has a very similar mind to Harry, she has not entangled herself in the same web of self-denying of joys as Harry has, motivated from a claimed intellectual high-ground. Compared to him, she is freer, happier and truer to herself. She keeps pushing for him to get out of his shell through the change that she brings; with the dancing, by introducing him to his lover, by introducing him to casual drug use (at the time no doubt an outrage for many readers). She makes him practise dancing with the goal of attending the Fancy Dress Ball; an event he has no desire to attend, but does so anyway due to her demands.

During a talk Harry and Hermine discuss how things have unravelled lately, and whether the previously miserable Harry is now content with life and his lover Maria. He has learned much and his character has developed. Yet he is not content; even though what he has is beautiful and delightful, he wants more: "I am not content with being happy. I was not made for it. It is not my destiny. [...] The unhappiness I need and long for is different. It is of the kind that will let me suffer with eagerness and lust after death."14 Hermine recognises his feelings, but asks what he has against the happiness that he has found with Maria, to which Harry replies "I have nothing against it. [...] But I suspect that it can't last. This happiness leads to nothing either. It gives content, but content is no food for me. It lulls the Steppenwolf to sleep and satiates him. But it is not a happiness to die for. [...] My happiness fills me with content and I can bear it for a long while yet. But sometimes when happiness leaves a moment's leisure to look about me and long for things, the longing I have is not to keep this happiness forever, but to suffer once again, only more beautifully and less meanly than before. I long for the sufferings that make me ready and willing to die". They talk about their role in the world, and Harry is impressed and relieved to have found someone of Harmine's intellect and sharpness of vision.15

Finally, the night of the Fancy Dress Ball came. Harry did his preparations and with much reluctance he eventually dragged himself to the hall of the event. He did not recognize Hermine or Maria at the event, although they were supposed to be there in the crowd somewhere. He did an earnest attempt at making himself at ease, but was unable to do so. The place was to him unfamiliar, unfriendly, and unnerving. The Steppenwolf was behind him, and neither the people, activities nor the wine in there pleased him. Finally, he found Hermine in the basement, in a room themed as hell. The previously unbearable night quickly takes a different turn. With Hermine by his side, inhibitions are loosened, the night becomes an adventure and he vibrates and resonates with the ball that shortly before made him so miserable. He danced and interacted with his peers. He experiences the downfall of individuality and instead becomes one with the crowd.16 Morning came, the ball guests left one by one, and Harry and Hermine did a last dance, knowing that they belonged together. Pablo came, and they moved to a different room and took drugs together.

Under the influence of the drugs, Harry finds himself in the long sought after Magic Theatre, that had been hinted at during several surrealistic encounters throughout the novel. It is not reality, but images in his own soul that he experiences there. In the Magic Theatre, there were many doors, "and behind each door exactly what you seek awaits you." Pablo instructs Harry that "You have no doubt guessed long since that the conquest of time and the escape from reality, or however else it may be that you choose to describe your longing, means simply the wish to be relieved of your so-called personality. That is the prison where you lie. [...] You are here in a school of humor. You are to learn to laugh. Now, true humor begins when a man ceases to take himself seriously."

Harry visits many doors and have different experiences all related to his personality, but in the last of the doors, he finds Pablo and Hermine lying naked and sleeping, after having had sex. In his pocket, Harry found a knife, and as Hermine had once instructed him, he stabbed her to death. Mozart, his great idol, entered the room and questioned Harry and his deed. Harry tries to defend himself, saying that it was Hermine's wish and something that brought him much sorrow, but Mozart is not buying this explanation, and only now it occurs to Harry that he has not questioned this wish of Hermine, nor where the idea might have come from. Mozart scolds him: "You have made a frightful history of disease out of your life, and a misfortune of your gifts".

A trial is held for Harry, and since he knows what he has done, he is ready for his punishment, facing the guillotine in front of him. The prosecutor states that Harry is "accused and found guilty of the willful misuse of our Magic Theatre. Haller has not alone insulted the majesty of art in that he confounded our beautiful picture gallery with so-called reality and stabbed to death the reflection of a girl with the reflection of a knife; he has in addition displayed the intention of using our theater as a mechanism of suicide and shown himself devoid of humor. Wherefore we condemn Haller to eternal life". Harry is thus not executed, and finds himself in Mozart's company again, who like before scolds him, telling him that "You have heard your sentence. [...] You are uncommonly poor in gifts, a poor blockhead, but by degrees you will come to grasp what is required of you. You have got to learn to laugh. [...] You are ready to stab girls to death. [...] When it's a question of anything stupid and pathetic and devoid of humor or wit, you're the man, you tragedian. Well, I am not. I don't care a fig for all your romantics of atonement. You wanted to be executed and to have your head chopped off, you lunatic! For this imbecile ideal you would suffer death ten times over. You are willing to die, you coward, but not to live".

It is revealed that the dead body was an illusion of the Magic Theatre, and not the real Hermine. Mozart is transformed into Pablo, and Harry understands the nature of the place. Pablo welcomes Harry to visit the Magical Theatre again, but also tells him that he was expecting more from him. "You forgot yourself badly. You broke through the humor of my little theater and tried to make a mess of it, stabbing with knives and spattering our pretty picture-world with the mud of reality. That was not pretty of you". Harry promises himself to try life's game again and one day be better at it, and one day learn to laugh.

Setting

The novel takes place and was written in Germany in the 1920s, and these were no doubt special times. The Great War had ended less than ten years earlier, and modernity and traditional values started clashing more and more it seems. There was economic turmoil. The fascists were gathering strength and the Bolsheviks as well. The American influences of culture and indeed people were ongoing.

In hindsight we of course know that the twenties was a build-up to the next war in the forties, after the fascists had seized and consolidated power. It was still surprising to me, however, to read about how the book talks with utter certainty about the war that is yet to break out. Harry and Hermine have a conversation about the matter.

Harry: "The next war draws nearer and nearer, and it will be a good deal more horrible than the last. All that is perfectly clear and simple. Any one could comprehend it and reach the same conclusion after a moment's reflection. But nobody wants to. Nobody wants to avoid the next war, nobody wants to spare himself and his children the next holocaust if this be the cost. To reflect for one moment, to examine himself for a while and ask what share he has in the world's confusion and wickedness—look you, nobody wants to do that. And so there's no stopping it, and the next war is being pushed on with enthusiasm by thousands upon thousands day by day. It has paralysed me since I knew it, and brought me to despair. I have no country and no ideals left. All that comes to nothing but decorations for the gentlemen by whom the next slaughter is ushered in. There is no sense in thinking or saying or writing anything of human import, to bother one's head with thoughts of goodness—for two or three men who do that, there are thousands of papers, periodicals, speeches, meetings in public and in private, that make the opposite their daily endeavor and succeed in it too."

Hermine: "There you're right enough. Of course, there will be another war. One doesn't need to read the papers to know that. And of course one can be sad about it, but it isn't any use. It is just the same as when a man is sad to think that one day, in spite of his utmost efforts to prevent it, he will inevitably die. The war against death, dear Harry, is always a beautiful, noble and wonderful and glorious thing, and so, it follows, is the war against war. But it is always hopeless and quixotic too."

Harry: "That is perhaps true, but truths like that—that we must all soon be dead and so it is all one and the same—make the whole of life flat and stupid. Are we then to throw everything up and renounce the spirit altogether and all effort and all that is human and let ambition and money rule forever while we await the next mobilization over a glass of beer?"

Hermine: "You shan't do that. Your life will not be flat and dull even though you know that your war will never be victorious. It is far flatter, Harry, to fight for something good and ideal and to know all the time that you are bound to attain it. Are ideals attainable? Do we live to abolish death? No—we live to fear it and then again to love it, and just for death's sake it is that our spark of life glows for an hour now and then so brightly."

References and Quotes

-

"This affliction was not due to any defects of nature, but rather to a profusion of gifts and powers which had not attained to harmony. I saw that Haller was a genius of suffering and [...] he had created within himself with positive genius a boundless and frightful capacity for pain. I saw at the same time that the root of his pessimism was not world-contempt but self-contempt; for however mercilessly he might annihilate institutions and persons in his talk he never spared himself. It was always at himself first and foremost that he aimed the shaft, himself first and foremost whom he hated and despised. [...] As for others and the world around him he never ceased in his heroic and earnest endeavor to love them, to be just to them, to do them no harm, for the love of his neighbor was as deeply in him as the hatred of himself." ↩

-

"Looked at with the bourgeois eye, my life had been a continuous descent from one shattering to the next that left me more remote at every step from all that was normal, permissible and healthful. The passing years had stripped me of my calling, my family, my home. I stood outside all social circles, alone, beloved by by none, mistrusted by many, in unceasing and bitter conflict with public opinion and morality; and though I lived in a bourgeois setting, I was all the same an utter stranger to this world in all I thought and felt. Religion, country, family, state, all lost their value and meant nothing to me any more." ↩

-

"Compared with Bach or Mozart and real music it was, naturally, a miserable affair; but so was all our art, all our thought, all our makeshift culture in comparison with real culture. [...] Was all that we called culture, spirit, soul, all that we called beautiful and sarced, nothing but a ghost long dead, which only fools like us took for true and living?" ↩

-

"Every age, every culture, every custom and tradition has its own character, its own weakness and its own strength, its beauties and ugliness; accepts certain sufferings as matters of course, puts up patiently with certain evils. Human life is reduced to real suffering, to hell, only when two ages, two cultures and religions overlap. A man of the Classical Age who had to live in medieval times would suffocate miserably just as a savage does in the midst of our civilisation. Now there are times when a whole generation is caught in this way between two ages, two modes of life, with the consequence that it loses all power to understand itself and has no standard, no security, no simple acquiescence." ↩

-

"It cannot be denied that he was generally very unhappy; and he could make others unhappy also, that is, when he loved them or they him. For all who got to love him, saw always only the one side in him. Many loved him as a refined and clever and interesting man, and were horrified and disappointed when they had come upon the wolf in him. And they had to because Harry wished, as every sentient being does, to be loved as a whole and therefore it was just with those whose love he most valued that he could least of all conceal and belie the wolf. There were those, however, who loved precisely the wolf in him, the free, the savage, the untamable, the dangerous and strong, and these found it peculiarly disappointing and deplorable when suddenly the wild and wicked wolf was also a man, and had hankerings after goodness and refinement, and wanted to hear Mozart, to read poetry and to cherish human ideals." ↩

-

"Only, through this virtue, he was bound the closer to his destiny of suffering. It happened to him as it does to all; what he strove for with the deepest and most stubborn instinct of his being fell to his lot, but more than is good for men. In the beginning his dream and his happiness, in the end it was his bitter fate. The man of power is ruined by power, the man of money by money, the submissive man by subservience, the pleasure seeker by pleasure. He achieved his aim. He was ever more independent. He took orders from no man and ordered his ways to suit no man. Independently and alone, he decided what to do and to leave undone. For every strong man attains to that which a genuine impulse bids him seek. But in the midst of the freedom he had attained Harry suddenly became aware that his freedom was a death and that he stood alone. The world in an uncanny fashion left him in peace. Other men concerned him no longer. He was not even concerned about himself. He began to suffocate slowly in the more and more rarefied atmosphere of remoteness and solitude. For now it was his wish no longer, nor his aim, to be alone and independent, but rather his lot and his sentence. The magic wish had been fulfilled and could not be cancelled, and it was no good now to open his arms with longing and goodwill to welcome the bonds of society. People left him alone now. It was not, however, that he was an object of hatred and repugnance. On the contrary, he had many friends. A great many people liked him. But it was no more than sympathy and friendliness. He received invitations, presents, pleasant letters; but no more. No one came near to him. There was no link left, and no one could have had any part in his life even had anyone wished it. For the air of lonely men surrounded him now, a still atmosphere in which the world around him slipped away, leaving him incapable of relationship, an atmosphere against which neither will nor longing availed." ↩

-

"There was nothing to charm me or tempt me. Everything was old, withered, grey, limp and spent, and stank of staleness and decay. [...] How had I, with the wings of youth and poetry, come to this? Art and travel and the glow of ideals — and now this! How had this paralysis crept over me so slowly and furtively, this hatred against myself and everybody, this deep-seated anger and obstruction of all feelings, this filthy hell of emptiness and despair." ↩

-

"I felt distinctly that my hosts were not at their ease either and that their liveliness was forced, whether it was that I had a paralyzing effect on them or because of some other and domestic embarassment. There was not a question they put to me that I could answer frankly, and I was soon fairly entangled in my lies and wrestling with my nausea at every word." ↩

-

"for it was at once clear to me that this disagreeable evening had much more significance for me than for the indignant professor. For him, it was a disillusionment and a petty outrage. For me, it was a final failure and flight. It was my leave-taking from the respectable, moral and learned world, and a complete triumph for the Steppenwolf. I was sent flying and beaten from the field, bankrupt in my own eyes. I had taken leave of the world in which I had once found a home the world of convention and culture." ↩

-

"Haste makes no speed. My resolve to die was not the whim of an hour. It was the ripe, sound fruit that had grown slowly to full size, lightly rocked by the winds of fate whose next breath would bring it to the ground." ↩

-

"Just as the gramophone contaminated the esthetic and intellectual atmosphere of my study and just as the American dances broke in as strangers and disturbers, yes, and as destroyers, into my carefully tended garden of music, so, too, from all sides there broke in new and dreaded and disintegrating influences upon my life that, till now, bad been so sharply marked off and so deeply secluded. The Steppenwolf treatise, and Hermine too, were right in their doctrine of the thousand souls. Every day new souls kept springing up beside the host of old ones; making clamorous demands and creating confusion; and now I saw as clearly as in a picture what an illusion my former personality had been. The few capacities and pursuits in which I had happened to be strong had occupied all my attention, and I had painted a picture of myself as a person who was in fact nothing more than a most refined and educated specialist in poetry, music and philosophy; and as such I had lived, leaving all the rest of me to be a chaos of potentialities, instincts and impulses which I found an encumbrance and gave the label of Steppenwolf. Meanwhile, though cured of an illusion, I found this disintegration of the personality by no means a pleasant and amusing adventure. On the contrary, it was often exceedingly painful, often almost intolerable." ↩

-

"Hermine: 'You are surprised that I should be unhappy when I can dance and am so sure of myself in the superficial things of life. And I, my friend, am surprised that you are so disillusioned with life when you are at home with the very things in it that are the deepest and most beautiful, spirit, art, and thought! That is why we were drawn to one another and why we are brother and sister. I am going to teach you to dance and play and smile, and still not be happy. And you are going to teach me to think and to know and yet not be happy. Do you know that we are both children of the devil?' ↩

-

"Hermine: 'You like me, [...] because I have broken through your isolation. I have caught you from the very gates of hell and wakened you to a new life. But I want more from you—much more. I want to make you fall in love with me. [...] I'm as little in love with you as you with me. But I need you as you do me. You need me now, for the moment, because you're desperate. You're dying just for the lack of a push to throw you into the water and bring you to life again. You need me to teach you to dance and to laugh and to live. But I need you, not today—later, for something very important and beautiful too. When you are in love with me I will give you my last command and you will obey it, and it will be the better for both of us. [...] You won't find it easy, but you will do it. You will carry out my command and — kill me.' [...] I had even guessed what her last command was before she said it and was horrified no longer. All that she said sounded as convincing to me as a decree of fate. I accepted it without protest." ↩

-

"I had learned from [Maria], once more before the end, to confide myself like a child to life's surface play, to pursue a fleeting joy, and to be both child and beast in the innocence of sex, a state that (in earlier life) I had only known rarely and as an exception. The life of the senses and of sex had nearly always had for me the bitter accompaniment of guilt, the sweet but dread taste of forbidden fruit that puts a spiritual man on his guard. Now, Hermine and Maria had shown me this garden in its innocence, and I had been a guest there and thankfully. But it would soon be time to go on farther. It was too agreeable and too warm in this garden. It was my destiny to make another bid for the crown of life in the expiation of its endless guilt. An easy life, an easy love, an easy death—these were not for me." ↩

-

"Hermine: 'You [Harry] have a picture of life within you, a faith, a challenge, and you were ready for deeds and sufferings and sacrifices, and then you became aware by degrees that the world asked no deeds and no sacrifices of you whatever, and that life is no poem of heroism with heroic parts to play and so on, but a comfortable room where people are quite content with eating and drinking, coffee and knitting, cards and wireless. And whoever wants more and has got it in him—the heroic and the beautiful, and the reverence for the great poets or for the saints—is a fool and a Don Quixote. Good. And it has been just the same for me, my friend. I was a gifted girl. I was meant to live up to a high standard, to expect much of myself and do great things. I could have played a great part. I could have been the wife of a king, the beloved of a revolutionary, the sister of a genius, the mother of a martyr. [...] Life, thought I, must in the end be in the right, and if life scorned my beautiful dreams, so I argued, it was my dreams that were stupid and wrong headed. [...] You are much too exacting and hungry for this simple, easygoing and easily contented world of today. You have a dimension too many. Whoever wants to live and enjoy his life today must not be like you and me. Whoever wants music instead of noise, joy instead of pleasure, soul instead of gold, creative work instead of business, passion instead of foolery, finds no home in this trivial world of ours—'" ↩

-

"But today, on this blessed night, I myself, the Steppenwolf, was radiant with this smile. I myself swam in this deep and childlike happiness of a fairy tale. I myself breathed the sweet intoxication of a common dream and of music and rhythm and wine and women—I, who had in other days so often listened with amusement, or dismal superiority, to its panegyric in the ballroom chatter of some student. I was myself no longer. My personality was dissolved in the intoxication of the festivity like salt in water" ↩

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons