Cubic Steric Overlap Detector

When modelling proteins, or when docking a pair of proteins together, one might want to test whether the solution is free from steric clashes. That is, when considering atoms to be hard spheres, one wants to know whether any atoms are so close together that the spheres representing the atoms intersect in 3-D. This program will detect any such steric overlaps between two proteins read from Protein Data Bank files (*.pdb files). Proteins are complicated 3-D structures, and are often "folded" in such ways that it would be very complicated to predict whether an arbitrary atom is close to another in the molecule.

The problem is from an old university assignment given by my professor. A few constraints applied to the problem. All atoms could be assumed to have a radius of 2.0 Å. The task was to minimise the number of atom-atom comparisons. Any pre-processing was allowed, and any data structures could be used in order to reduce the number of atom-atom comparisons required. Thus, the overall design goal of this program is to have as few atom-atom comparisons as possible.

Since the task is to minimise the number of atom-atom comparisons and any data structures could be used, I figured that some data structure with a lookup of , such as a hash table, would be optimal. If the coordinates of every atom in protein A are used as keys in a hash table, one could just loop through the coordinates of every atom in protein B and do an

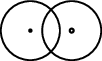

lookup to see if there is a clash for that coordinate. A problem quickly arises though; in the *.pdb files where the atom data comes from, the position of the atoms are given by the coordinates of the atom centres. Thus, two atoms can clash (i.e. have their volumes intersect in 3-D) if they are close, despite not being at identical positions. A 2-D sketch of this is shown in Figure 1.

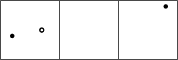

This makes a hash table unsuited for this purpose; two different coordinates would not map to the same atom. However, what if a region or volume could be hashed, rather than coordinates? Consider the 2-D drawing in Figure 2.

Each rectangle is one area that could somehow be used as the key to the hash table, and each area can contain more than one atom whose coordinates fall inside it. In Figure 2, the atoms from protein A are drawn in black and the atoms from protein B are drawn in white. In this example, the first area has one atom from protein A and one from protein B inside; i.e. a clash. The second area is empty, and the third has one atom from protein A.

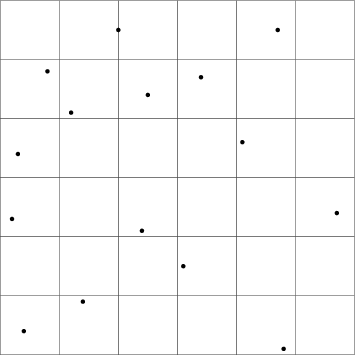

An illustration of what a larger 2-D plane of one protein could look like is shown in Figure 3. Each area could be enumerated in some way, for instance from the upper left corner. By assigning each area a predictable number, this ordinal can be used as the hash table key.

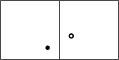

The size of the areas' sides equals the diameter of the largest atom, in this case 4.0 Å. Notice that a clash can happen even though the atoms are not in the same area, however. Consider Figure 4, where an atom from protein A is in the first area, and an atom from protein B is in the second. Given that the side of the area is 4.0 Å, the atoms are close enough to clash, despite being in different areas.

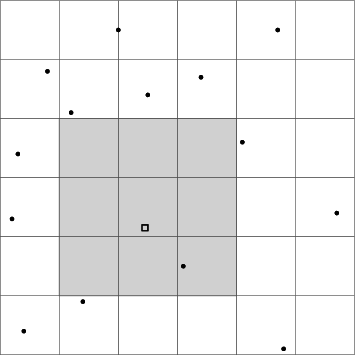

In order to find all potential clashes for an atom that resides in some area, the areas adjacent to it will have to be searched as well. In the 2-D example, this would be areas to look in. Figure 5 illustrates the regions that have to be searched, if the atom to find clashes for is denoted by the small square.

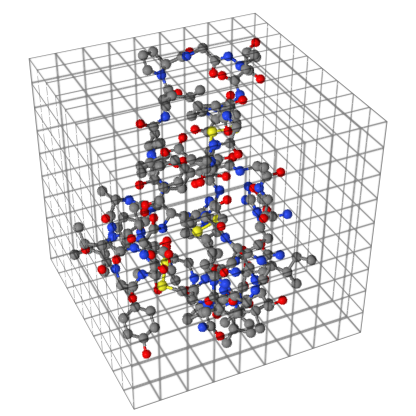

Of course, the proteins are in 3-D. Thus, a protein is divided into a space consisting of cubes with the sides being of length 4.0 Å. An illustration of the Crambin protein (1CRN) inside a space is shown in Figure 6. Note that this is an illustration of the principle and the cubes are not to scale.

The space spanned by the atoms of protein A would be divided into cubes, and so would the atoms of protein B. Thus, similar to Figure 5, for a given atom in one of the proteins, the cube that it falls inside will be calculated, and the adjacent cubes of the other protein will be looked in for a clash.

Thus, every atom of protein A will be assigned into the corresponding cube, and the cube-atom pair will be placed in a hash table. When searching for clashes, we can now go through every atom of protein B, find the 27 adjacent cubes of it and look them up in the hash table. While 27 look-ups for an atom might seem costly, the number is constant no matter the size of the proteins. This solution is thus .

I received acclaim and the highest grade for the solution, and was afterwards made aware that it is similar to to the "cubing" approach suggested by professor Cyrus Levinthal, who is considered the father of computer graphical display of protein structure.

The code is available at my GitHub account.

Screenshot of the program:

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons